Experts debate the origin of the park’s name, “Acadia.” Some believe the word derives from the Arcadia region in Greece, prized for its unspoiled wilderness. Over time, the “r” in the reference dropped—giving rise to the label “Acadia.” Others attribute the name to the word “L’Acadie,” which potentially stems from the French version of a Wabanaki Indian word meaning “the place.” Rumors suggest that the first European settlers to Mount Desert Island may have also translated this term as “heaven on Earth.”

When I first applied—sight unseen—to the Artist-in-Residence (AiR) program with Acadia National Park, I called my fortunate opportunity simply an escape. The new adventure promised a peaceful refuge to create my art in a place so distant and so different from my home in Arizona. Although the name suggested a captivating place, I never intended to fall in love.

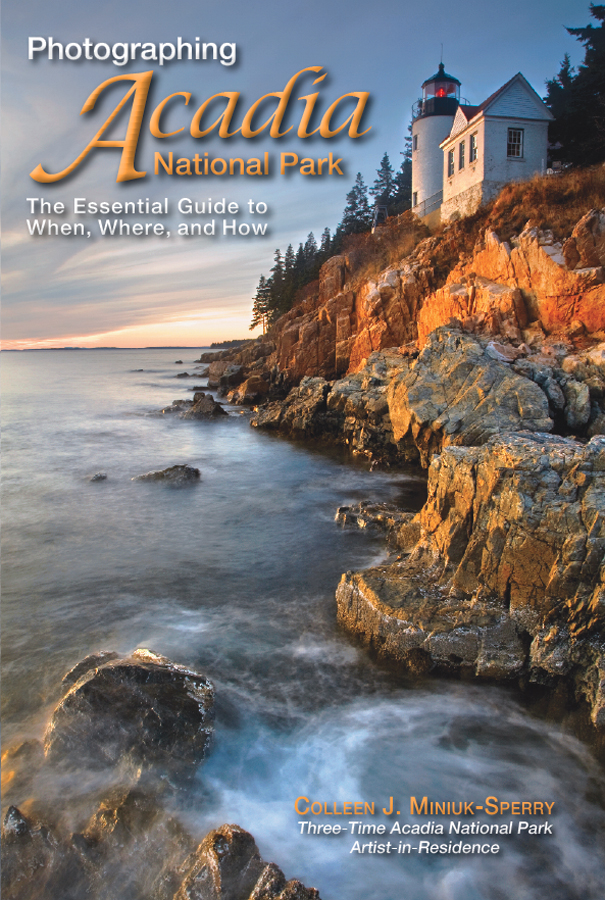

During my first residency in November 2009, I set out to see all the popular places I had previously seen in other people’s pictures—the iconic Boulder Beach, the classic view from the top of Cadillac Mountain, and the majestic Bass Harbor Head Lighthouse. These recognizable scenes draw attention from photographers for good reason—they offer striking beauty! I wanted to see them with my own eyes, through my own lens, and attempt to put my own spin on these admired compositions at a time when most people do not visit the park.

For the abundance of photographic opportunities awaiting at the end of my 3,000-mile cross-country journey, I packed my two Canon 5DMII cameras, four lenses (16-35mm, 24-105mm, 100-400mm, 100mm macro), extension tubes, a polarizer, graduated neutral density filters, reflector, diffuser, tripod, and cable release. (Unfortunately, the mule to carry it all did not fit in my suitcase!) Upon arriving in Portland, Maine, I made a quick stop at Hunt’s Photo and Video to pick up additional batteries and memory cards.

As expected for the time of year, the vibrant autumn leaves had fallen, the seeds of brilliant wildflowers were hidden in the damp soil, and the first crisp snow had not yet draped the coastal landscape. During this time of transition, it seemed the weather could not make up its mind. Sunshine, clouds, rain, and fog occurred throughout my stay—sometimes all on the same day! Chasing the fleeting light for three weeks, though, left a memorable impression…and a feeling that I had run out of time at this magical place too quickly.

Thankfully, I returned to the park for a second residency in October 2010, when the park bustles with “color chasers.” The Great Fire of 1947 scorched more than 17,000 acres of the east side of Mount Desert Island’s spruce and fir forests, making way for healthy stands of deciduous trees to sprout out of the charred landscape. As a result, following the change in seasons, screaming autumn colors cause the park’s tableau to glow every shade of red, orange, and yellow imaginable starting the first week of October.

In search of the kaleidoscope of colors, I balanced my time between reworking the old classics and seeking out lesser-known locations. Serving as less crowded alternatives to the more popular Cadillac Mountain summit, the sweeping views from atop Day Mountain and Gorham Mountain showcased a blanket of color from birches, beeches, aspens, oaks, sumacs, and maples. Quiet places like Beaver Dam Pond, Jesup Trail, and the Tarn came alive in a colorful symphony. No matter the location, the seasonal shift made it very difficult to make a bad image so long as you had your camera turned on, lens cap off, and a memory card loaded!

After two residencies, I knew I had found heaven on Earth on the Maine coast and yearned to see more. I therefore returned to the park in June to experience the freshness of late spring and early summer. Rhodora, oxeye daisies, and non-native lupines transformed the Great Meadow into wildflower bliss. Asticou Azalea Garden, which resides outside of the park (but nonetheless a “can’t miss” spot while visiting the area) teemed with rhododendrens, azaleas, and laurels flaunting their blooms. Blue flag iris and sedges swayed in the wind beneath birch dotted with florescent-green leaves at Sieur de Monts.

Long pants, long sleeved-shirts, and bug spray helped to keep the black flies, mosquitoes, and “no-see-ums” at bay as I extensively explored during the 17-hours of sunlight. Although my life motto (and the name of my blog) is “You can sleep when you’re dead,” I felt more creatively engaged and observant after taking a refreshing nap in the middle of the long summer day.

With each visit to Acadia, I brought home more questions than answers and more ideas than photographs. As my understanding and emotional connection with the park increased, I sought to record a more complete visual story by exploring even more new locations on a more profound, creative level. I wanted to find the smaller, less obvious things that contributed to making the park so special. In hopes I would also have the chance to see how Acadia as a place and I as an artist had changed from the previous years, I submitted my application for an unprecedented third Artist-in-Residency. As Acadia’s first winter AiR, I rediscovered paradise for four weeks during January and February 2013 in a new light and season. I also found truth in Heraclitus’ quote: “No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man.”

While trudging along in my warm winter boots and YakTrax on the snowy coastline, I still felt the same sense of awe I had experienced so many times before. Ever-changing weather produced many fiery skies at first and last light—ideal conditions that certainly fed my wide-angle lens addiction.

However, the various types of ice—frazil, grease, and pancake—collecting on the water’s edge absolutely captivated me! Seeing this new fascination was not a matter of simply switching lenses or looking at other peoples’ previous pictures, though. Instead, I simply followed my curiosity wherever it led me, knowing that if I expressed enthusiasm for a subject upon observing it, I had the makings of an emotionally charged image—one which would convey a unique, personal visual message in a place I and so many have traveled before.

Because of the smaller scenes striking my senses, my telephoto and macro lens (often paired with extension tubes) served as my “go to” lenses at winter wonderland spots like West Pond Cove on the Schoodic Peninsula, Thompson Island in between the mainland and Mount Desert Island, and Sand Beach on Mount Desert Island. In addition, when the nasty nor’easter (dubbed Winter Storm Nemo by the Weather Channel) blew through the region, I tucked my telephoto lens safely inside my rain cover, bundled up in all the winter clothes I owned (in hindsight, I wish I had brought ski goggles), and then watched with a mix of wonder and terror the monster waves pound the granite ledges at Schoodic Point as the howling wind carelessly tossed cotton-ball puffs of snow every which way.

After considerable wandering around Mount Desert Island and the Schoodic Peninsula, I craved an even more raw, remote, and off-the-beaten path adventure. Located about 15 miles southwest of Mount Desert Island as the crow flies, the small island of Isle au Haut all but guaranteed a memorable photographic trip without having to compete for space with other photographers.

Getting to solitude, however, required much advanced planning. Though a single day spent on the island (which is how most visitors experience this isolated section of the Acadia) will not disappoint, shutterbugs wishing to capture sunrise or sunset light will inevitably miss the optimal times for landscape-style photography during a day trip. I recommend spending at least three days or longer, either at the primitive Duck Harbor campground (reservations required), the Keeper’s House Inn, or by renting a home.

After the first-come, first-serve passenger-only mail boat ferried us and our piles of clothes, groceries, and camera gear from Stonington to the Town Landing, we settled into our rented cottage on Rich’s Cove for a week-long stay. Our rental agreement also afforded the use of bikes and a vehicle, both of which helped travel the rough, single-lane dirt park road and around the six-mile long by two-mile wide isle.

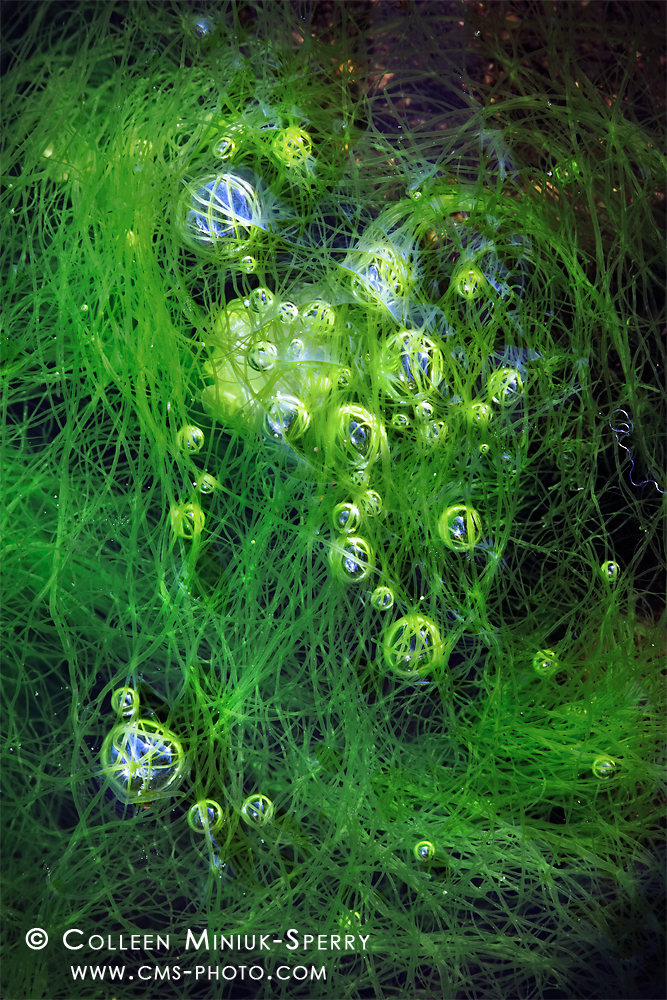

Our reward for our efforts? Solitude in unspoiled spruce forests, mountain summits, bogs, marshes, a freshwater pond, and some of the most pristine coastline within all of Acadia. I felt like a kid in a candy store as I studied bubbles in tide pools along Eben’s Head Trail, marveled at the unexplainable patterns in the granite along the Western Head Trail, and photographed the crashing waves along the rugged Cliff Trail. I cannot get back to Isle au Haut soon enough!

After spending more than 120 magical days across all seasons in four years in the park (thanks to the AiR program, Arizona Highways Photography Workshops, and personal trips), I felt this burning urge to run to the top of Cadillac Mountain and loudly yell so everyone in the world could hear, “COME TO ACADIA! COME TO ACADIA!”

Of course, to do so would violate the “Leave No Trace” principle of being considerate to others and maintaining quiet (and likely annoy a whole lot of people!) so I decided to write a book instead. Consider my new guide Photographing Acadia National Park: The Essential Guide to When, Where, and How my invitation to you to experience, enjoy, and photograph Acadia through your own lens.

Mother Nature has left a world of wonder here while those who came before us have provided celebrated cultural and historical treasures. You need only to bring your camera and curiosity to record your own stories and experiences in this diverse place.

Roll up your pant legs and get your feet wet at Sand Beach. Listen carefully to the cobble clapping for you as the waves splash against Little Hunters Beach. Ponder what life must have been like for the rusticators as you stroll along the carriage roads. Photograph in horizontal rain atop Cadillac Mountain. Gaze in awe at the Milky Way above Jordan Pond. In doing so, I hope you find your place in “the place” and discover your own “heaven on Earth” at Acadia National Park.

But be forewarned! When talking about the magic of Acadia, locals and visitors alike often suggest there is something about this coastal park that grabs a hold of your heart and does not let go. Acadia has yet to let go of mine, and I hope it does not let go of yours either.

Colleen Miniuk-Sperry escaped her software engineering job at Intel Corporation seven years ago to pursue her dream career as an outdoor photographer, writer, publisher, instructor, and public speaker. Her credits include National Geographic calendars, Arizona Highways, Outdoor Photographer, AAA Highroads, AAA Via, and more. She also leads photography workshops with Arizona Highways Photography Workshops, Maine Media Workshops+College, The Nature Conservancy, Through Each Others Eyes, and private clients. To see her work, workshops, books, and blog and to sign up for her quarterly newsletter, visit www.cms-photo.com.